Identifying Genetic Drivers of Childhood Leukemia:

ARUP’s Cytogenetics Team Leverages Expertise To Provide Answers for Patients in Children’s Oncology Group Trials

For children who are diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML), understanding the driver of disease can drastically affect their outcomes.

As a laboratory certified by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), an organization dedicated to childhood cancer research, ARUP’s Cytogenetics Laboratory performs testing to determine the genetic abnormalities that drive cancer in the pediatric population. Through exhaustive effort, they apply their expertise and experience to contribute to improving outcomes for pediatric patients with cancer. ARUP processes a large percentage of COG cytogenetic testing for ALL and AML in the United States, averaging between 150 and 200 cases each year.

“In pediatric oncology, especially in cancer of the blood and bone marrow, knowing what the abnormality is cytogenetically allows providers to specifically treat what is driving the disease,” said Monica Theriot, MLS(ASCP)CMCGCM, the lab supervisor for the Cytogenetics Laboratory at ARUP.

AML and ALL are classified into different subtypes based on genetic abnormalities that drive disease, and treatment strategies vary accordingly.

The ARUP Cytogenetics Laboratory began joining in cytogenetic studies for COG clinical trial cases more than two decades ago. Through the dedicated efforts of medical directors and lab technologists, significant improvements have enhanced the lab’s performance when it comes to COG cases.

“Our work for cases in COG trials largely focused on improving the abnormality detection rate for pediatric B-ALL,” said Bo Hong, MD, FACMG, medical director of Cytogenetics and Genomic Microarray. “B-ALL is a predominant pediatric neoplasm, with 75% of cases occurring in children younger than six years old. Cytogenetic findings are crucial for diagnosis, treatment planning, and prognosis assessment. We carefully process and review each COG case, submitting the cytogenetic data to the COG committee for central review to ensure proper patient enrollment in COG trials.”

To be certified to perform testing for COG cases, participating laboratories are required to demonstrate an abnormality detection rate of at least 55%—a standard that ARUP far exceeds year after year.

Identifying cytogenetic abnormalities for these pediatric cancer cases is particularly challenging.

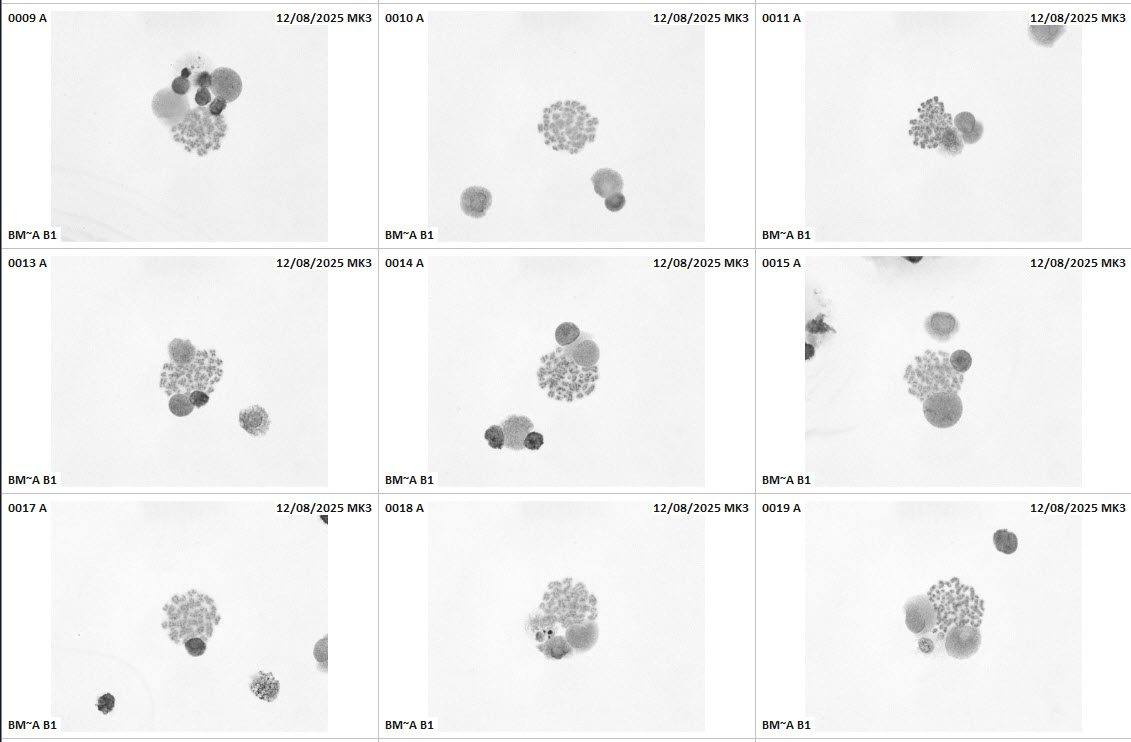

For example, in a standard case within the adult population, an abnormality can often be found within the first 20 cells that are analyzed. For COG cases, technologists often analyze hundreds of cells to detect just two abnormal cells, a finding that is required to establish clonality, said Theriot. As clonal diseases, ALL and AML derive from a mutated cell that propagates, giving rise to a cancerous cell population.

Pediatric cases pose additional challenges. Obtaining a sufficient bone marrow sample from a pediatric patient is difficult, and the quality of the metaphase cells in pediatric malignancies creates challenges in comparison to other types of malignancies that the team examines.

“The work we do can be grueling. Sometimes you spend hours and hours trying to find the answer, the abnormal clone, and still do not find it. You pour a lot of heart into the work, and at the end of the day, still have to sign it out as normal,” said Theriot. “Then there are those days where you do find that clone and know that you’re able to provide answers that are going to make a difference.”

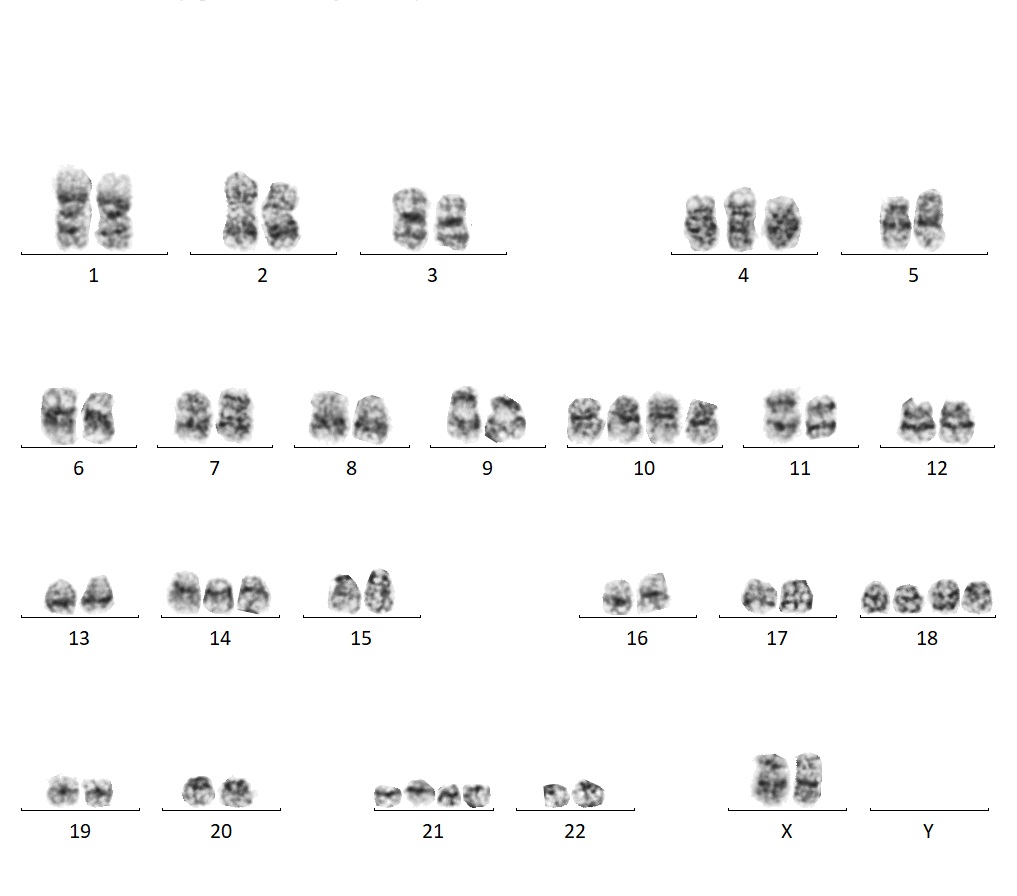

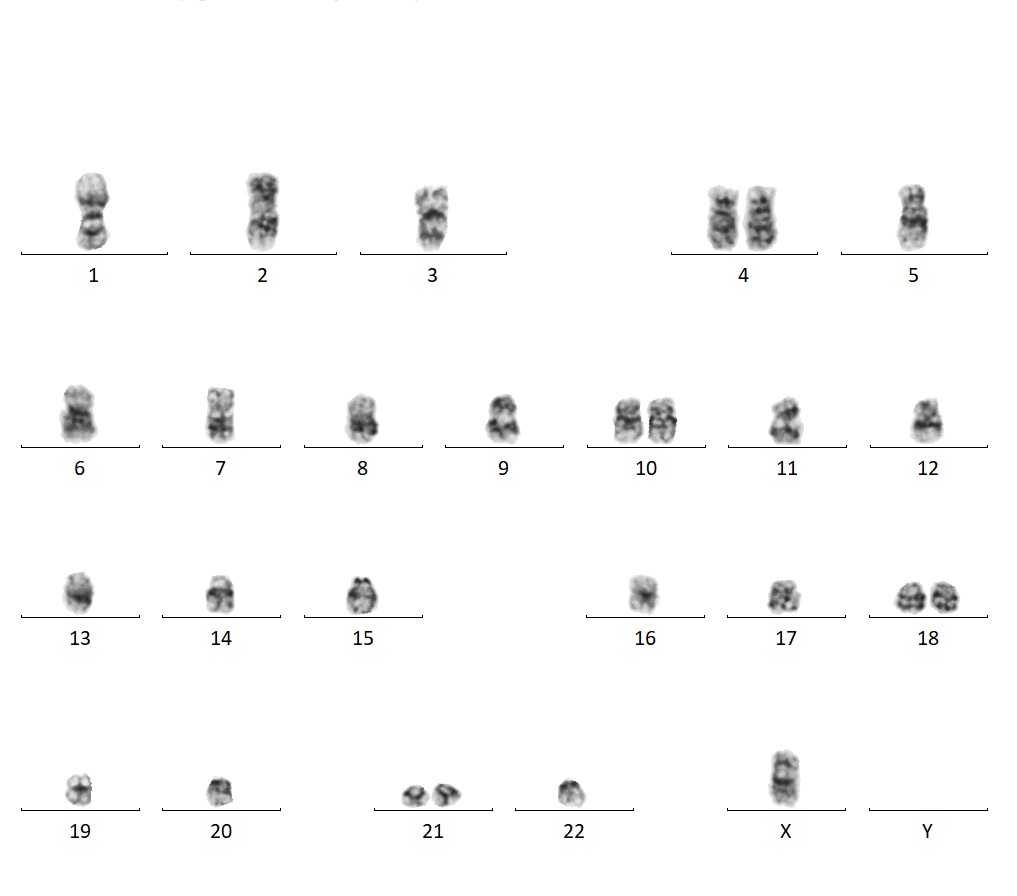

Some cases require multiple tests to accurately define the abnormality. For example, hypodiploidy, which is a loss of chromosomes, can appear as the opposite—hyperdiploidy, a gain in chromosomes.

“We can look at the karyotype and figure out that the gains are masking hypodiploidy,” Theriot said. “A cell line can essentially double and look like a hyperdiploid gain of chromosomes, when it is actually the doubling of a hypodiploid clone.”

While hyperdiploidy is associated with good prognosis, hypodiploidy is often associated with poor prognosis. Distinguishing the difference is critical for determining appropriate treatment.

“At the ARUP Cytogenetics Lab, we offer comprehensive testing, including karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and genomic microarray for COG cases to enhance diagnostic yield. Certain high-risk abnormalities, like masked hypodiploidy and intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21), can be missed or misinterpreted by karyotyping and FISH due to the suboptimal mitotic index and chromosome morphology as well as technical limits, impacting treatment and outcome. Therefore, we integrate genomic microarray, a crucial tool for diagnosing these specific abnormalities and cases with uninformative results from karyotyping and FISH,” Hong said.

ARUP has a dedicated team of experienced cytogenetic technologists who work on COG cases.

“Our team knows what they are looking for—how to dig into these cases and keep pushing until they find the answer,” Theriot said.

As a result of the efforts of the many who have contributed to better understanding and treatment of childhood cancers, survival rates have drastically improved.

For some childhood cancers, the increase in survival rates has been so dramatic that clinical studies are shifting to focus on minimizing the adverse effects of therapy.

“One of the challenges is that the therapy they use to achieve these good outcomes is severe, and the patients can have lifelong adverse effects, such as decrease in cardiac function, cognitive decline, emotional and mental health challenges, or damage to other organs,” said Rodney Miles, MD, PhD, medical director of Hematopathology at ARUP.

Now, studies are focused on determining whether the same outcome can be achieved with less intensive therapy.

Miles has been involved with COG since early in his career as a young investigator, and he is now a member of the COG committee for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

In 2011, Miles contributed to an international study to determine whether adding rituximab to the standard chemotherapy regimen improved event-free survival in children and adolescents with advanced-stage B-cell NHL. The study found that rituximab prolonged event-free survival, which was 93.9% at 3 years.

Miles, along with retired ARUP CEO Sherrie Perkins, MD, PhD, reviewed all of the U.S., Australian, and Canadian cases to confirm the diagnosis.

“This trial redefined the standard of care for mature B-cell NHL in children,” Miles said. “In fact, they had to stop the trial early.”

The new therapy demonstrated enough success that it became necessary to administer that therapy to all of the study participants rather than continue the trial.

Miles also serves as the COG vice chairman for faculty development, taking an active role in helping young investigators build their careers and become involved in COG.

“I’ve come full circle, from starting as a young investigator myself to having a role in engaging new young investigators,” Miles said. “It’s important that we prepare the next generation to continue the work of COG.”

In addition to cytogenetic testing, ARUP also performs COG-accredited testing to detect minimal residual disease in both blood and bone marrow in lymphoblastic leukemia cases, as well as markers to evaluate residual disease after CD19-targeted therapy.

“Every study keeps increasing the odds for these patients. To know that we are directly contributing and making a difference is so fulfilling,” said Theriot.